The Major’s last battle – the story of a golden Skeleton

The police didn’t have to break in - the neighbour had a key. On the floor they find the one that the call concerned and there is no need to hurry. An older gentleman living alone has quietly passed away in his apartment on Karlavägen in Stockholm and for the policemen it is one routine assignment amongst others.

It is in the middle of the summer in 1989 and the neighbour tells them that the dead man was Erland von Otter, a bachelor who had come to spend most of his adult life in the house and who had reached 86 years in the spring. The two neighbours had been popping over to each other on a daily basis and she had now called the police herself after having heard a thud from the friend’s apartment.

She was contented to do her friend this last favour but said that she was otherwise not related to, or part of the family. She did, however, believe to know that there was a letter from someone in the family lying on the deceased’s desk.

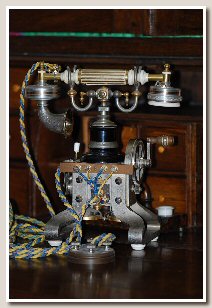

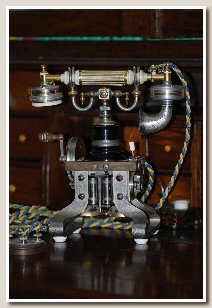

Gratefully, the policemen conclude that there are no signs of any crime. The apartment is tidy and filled with antiquities from a “better home”. In the living room there is a telephone of an ancient design, strangely gleaming of gold. Nothing, however, seems to be broken up or stolen.

Following a routine check by the coroner and telephone call or two to the deceased’s closest relatives, the case for the police would probably soon be closed. Life had had its course and we shall all wander that path. The representatives of law enforcement feel alleviated.

The distribution of the estate

In his later years, von Otter moved into a smaller apartment in the same building, and already then parts of his estate were distributed to other members of the extended family. They would be inheriting him in any event.

His last Will and Testament contained directions as to his wishes with regard to his estate that he left behind. Although the original Will was never found, the surviving children of his siblings and cousins could, following some discussion, nevertheless reach an agreement. That which no one wanted was left to be sold by the Stockholm City Auction House.

There were lots of different antiquities, amongst other things designer furniture, silver and books – objects which in most cases had followed von Otter’s branch of the von Otter family since the mid 19th century. At this point a number of things would continue down the family tree, others would disperse.

The estate included a peculiar telephone, a so-called Skeleton, albeit of a somewhat unusual design. Von Otter had always had it in sight and had not insignificantly cared for the family’s history, but now no-one knew anything about it. Reading the text on the telephone itself, it emerges that it was delivered to B. S. von Otter, the deceased’s grandfather, as a gift in 1892. Erland von Otter, in turn, jotted down a little note that the Decker Jewellers had mended the funnel on 8 June 1976 and charged 35 kr for it. Apparently, that piece of information was important to him.

The Auction House slapped a price tag of 2,000 kr on the telephone, i.e. the cost of Skeleton phones at the time, and it went to one of the first cousins - once removed, in Skåne, southern Sweden. The telephone would be left standing with him until it was handed in for auction in Malmö as a superfluous object. It no longer meant anything to the remote family and no greater consideration was spent on whether any value could be attached to it. Following a few turns, it eventually ended up in the Söderblomian collection in Lund.

The journey back

His eyesight was no longer at its best, and with painful relentlessness his ailments began to catch up with him, but grandfather Bror Samuel von Otter could nevertheless, at this time and with the seniority of his age, consider his duties in life to have been duly discharged.

He had passed the age of 78 years and carefully tended to the completion of his numerous assignments, and had also attempted to cater for his posthumous reputation. At least locally, no-one could have escaped hearing of him in the public life of the late 19th century.

His family was known from the end of the 16th century – knighted in 1691 – and had thenceforth come to foster many prominent military figures, county governors, government ministers and judges. Bror Samuel’s own father was captured by the enemy at the capitulation of Sveaborg in 1808. He then married into the Göta Kanal Company and became a Director of its Western District.

Bror Samuel grew up with three ambitious and successful brothers: Oscar Sebastian would make a career as a Member of Parliament in the Second Chamber, County Council Member, manor owner and Director. Carl Gustaf was a prominent marine officer, inventor of a flashing lighthouse beacon and appointed Marine Defence Minister. Fredrik Wilhelm, lastly, also he a highly ranked Marine Officer and Marine Defence Minister, Member of Parliament in both Chambers and even Prime Minister during a few years in the beginning of the 20th century.

It was with relatives – living and dead – to which he had to compare himself. A Swedish nobleman with the proudest of traditions, with a vocational duty to society, and history as a witness. And Bror Samuel had tried plenty to do his share.

The strong man of the City

Bror Samuel married in 1858 with Sofia Trädgårdh, a girl from the better and more educated families, and she came to give birth to four of his children.

At the same time, his civil career in his new home town Kristianstad took off, inspired as he was by his grandfather on his mother’s side, the industrious politician, businessman and channel constructor Berndt Santesson. Bror Samuel became Deputy Member of the Board for the Care of the Poor in 1858, Member of the Board of Kristianstad Sparbank 1858, Chamber of Finance 1861, Councillor 1862, Finance Director of the local Dairy Company 1871-76, Chairman of I.T. Liljedahls läder- och remfabriks-AB 1874-77, Chairman of the Gas and Water Works 1877-80, County Council Member 1883-91, CEO of Kristianstads Enskilda Bank 1867-98, Chairman of Kristianstad-Hessleholm Railroad 1888-98, CEO of Kristianstads City Hall AB 1886-93 and CEO of Torsebro krut- och stubinfabrik Company from 1875. This only to mention a few public appointments.

In the midst of this network of leading City men was the order of the Freemasons, and consequentially, Baron von Otter achieved one of the highest ranks in its hierarchy, Deputy Provincial Master of the Provincial Lodge in Kristianstad.

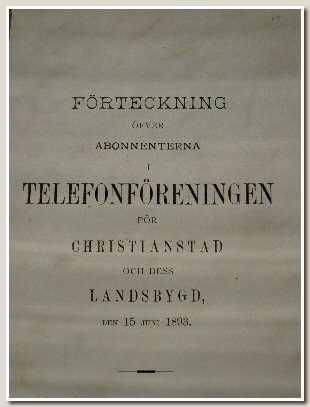

The telephone association and the battle for Skåne

The project would bear the same cooperative characteristics as the associations emerging in many other Swedish places at the time. The idea was to run a non-profit operation. Each member paid for his/her own telephone with a connection, and then the common operational expenses were divided up between them.

What would come to be unique about the “Telephone Association for Kristianstad and the surrounding rural areas " was that Posse succeeded in signing a cooperation contract with Telegrafverket, which meant that the state-owned telegraphy station staff handled the private association’s switchboard. This was opened for traffic on 1 April 1882 and Posse procured telephones from LM Ericsson in Stockholm on behalf of some 40 members.

But the person who in practice and for many years would be handling the network was the telephone constructor Mr Hilde Torbjörnsson, and the Board of Directors was made up of Cavalry Captain CG Stjernswärd, bookdealer Mr Hjalmar Möller and Baron and likewise CEO of the association, Bror Samuel von Otter, with the telephone number 19. Also the other subscribers seemed to have been mostly “Counts and Barons”, i.e. the financial cream of Kristianstad at the time.

The reasons were surely primarily financial – there was an apprehension that the costs would soar in the hands of the state – as already in the first clause of the association’s Charter, the object of which was "to maintain a telephone connection within the city and surrounding rural area on the cheapest conditions possible."

The state started with the acquisition of the Bell network in Malmö in 1882. Subsequently, new networks were connected in Lund and other places in Skåne, one after the other. Together they formed the basis of the so-called "Provincial Network of Skåne" which came to be Telegrafverket’s pride and joy.

The Association in Kristianstad was therefore an irritating obstacle for the expansion of the Provincial Network in the northeast and it was decided to break Mr von Otter’s network in competition, by building a parallel network of their own. The board, in turn, readily realised the advantages of giving up the fight and allowing themselves to be swallowed up by the Provincial Network, but the members were conservative. The annual fee of the association was 25 kr and Telegrafverket’s fee was 125 kr. Instead, in 1887, the association was to get a direct connection with a smaller network in Blekinge, which included Karlshamn, Ronneby and Landskrona. Later also Växjö and Alvesta.

Nevertheless, with stick and carrot, the state had set its mind to win the battle and signed a smaller network pooling agreement with the association. For an annual fee of 20 kr, the members would be entitled to make local telephone calls, but not regional ones. That way, it was hoped that the subscribers would gradually be enticed over. At the same time, the Bleking network was successfully expropriated through court litigation. After that, the association’s line eastward could simply be shut down and even the steadfast telephone association in Växjö saw itself forced to sell – although not the one in Kristianstad.

Storckenfeldt, whose energy level, according to his contemporaries, "probably more than once spilled over into ruthlessness ", conceded to send special couriers from Stockholm to negotiate with von Otter about a voluntary take-over, but von Otter’s demands were such as to rule out any agreement.

The anniversary of the association and von Otter

In the spring of 1892 Bror Samuel himself would reach 60 years of age and it is assumed that he now was at the peak of his powers. He played with verve the role as one of the most important men of Kristianstad. At the same time, the proud telephone association, with its approximately 160 members, was going to celebrate its 10-year anniversary.During this time, the conflict between the private network and Telegrafverket had reached a critical stage. The government would soon also be taking over the domestic telephone industry and have telephones be mass-produced for Sweden’s entire population. And yet again, the state put forward proposals about taking over the home-made network in north-eastern Skåne. The association called for a meeting to take place on 5 March and a reporter from the local paper, Nyaste Kristianstadsbladet, was present:

At the same time, it was decided to raise the salary of the protector of the network, Mr Torbjörnsson, from 2000 kr to 3000 kr, and also to award its flagman and CEO von Otter 500 kr as a "new expense ".

In the end, it was only von Otter’s association in the entire country, which had a network pooling agreement with Telegrafverket, but now, in 1897, the Director General submitted a notice to terminate the agreement, while at the same time dumping his own prices, down to the level that of the association. Everything to strangle the unruly once and for all.

The Director and his board now wanted to surrender and sell themselves to the government as expensively as they possibly could, but the members once again declined. The smaller rural associations, which had been tied to Kristianstad, yielded however one after the other, and soon the network was decimated to 290 stubborn subscribers in the city centre.

After almost 20 years, Bror Samuel von Otter finally arrived at the conclusion to resign and the members chose a more rabid leader, Count Adolf "Adde" Rosentwist.

Rosentwist continued to compete with the state and frenetically fight for his network in its simple-threaded form, which now also started to become completely outdated.

It was first after Adde’s death that the association gave up the resistance, and for a sum of 29000 kr sold its property and operation to the state in 1907. The purchase included 398 telephones from the city, and about 50 from the countryside.

Storckenfeldt had in practice, albeit posthumously, managed to create a state monopoly and his name appeared in the encyclopaedias, more specifically associated to "the expeditious and excellent development of the Swedish national telephony network in the 1890s."

The Baron’s posthumous legacy

His first-born daughter died at the age of seven years, as did his eldest son at almost eleven. The other daughter grew up, but passed away in the blossom of her youth, at 21 years of age, and his beloved Sofia died away from him following a 25-year marriage.

A second marriage lightened up his old age, but was childless. Now, there was only the single surviving son, with a military career ahead of him, and his children, a girl and a boy. That the male line of descent would die out with little Erland, he could not yet know.

He had had many appointments and received many honorary awards, but everything was so typically provincial, while the brothers could make a career on a national level. They were walking the corridors of real power, wielding executive authority and making decisions. It was quite simply they, and the ruthless Storckenfeldt, who would have their names entered into the encyclopaedias and the biography books. He, on the other hand, would soon long since be forgotten when the beefed-up obituary in Nyaste Kristianstadsbladet, and the considerably more modest item in Dagens Nyheter, had turned a yellow shade.

Whether von Otter’s aged thoughts actually went in this direction we, as latter-day onlookers, cannot know, or hardly even guess, but when searching for all of the material which could have retold his story, it doesn’t seem impossible that this was the case. He is mentioned in many books and in many archived documents, but only as a footnote, small references to the fact that he had existed, but no colourful statements, no special grand deeds or projects are associated to him in particular.

The brothers, on the other hand, can be read about comprehensively in many books; about all of their achievements, everything they thought and wanted to do. Or perhaps the case was that Bror Samuel himself actively chose to operate at the local level, or maybe his inherent ability didn’t make anything else possible – that we shall probably never know.

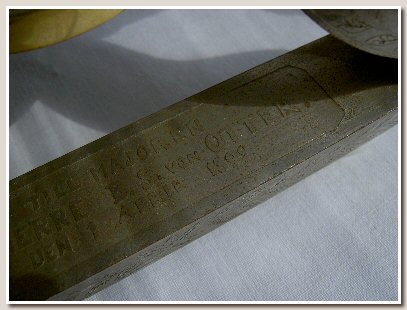

A Skeleton with inscriptions

As a prominent freemason, von Otter was awarded a knighthood in the exclusive Charles XII Order in 1899. He was therefore entitled to carry their beautiful Order Cross in red and gold, together with the magnificent insignia of the Vasa Order, the Sword Order and the Dannebrog Order, which he was already carrying. It is on account of this membership, and the diligent biographer Anton Anjou’s historical writings on the few knights, that we can come somewhat closer to his personality.

Apparently, it is the same "desk telephone with inscriptions for 1000 kr" as revealed by LM Ericsson’s ledger of 3 February 1892, that was delivered with a "hand set" at the end of March that same year. If one is to rely on the firm’s own notes, it was the first telephone with a hand set they had ever sold within the country, while the premier article was exported to Finland in the beginning of February the same year.

Most of the factory’s and the association’s archived documents have otherwise been lost, but it is thought that detailed instructions must have been issued about the new "top modern" model, von Otter’s nobility coat of arms, the beautiful engravings, the precious materials, the etched honorary credits and the cord’s Swedish colours. This was a manifestation of an exchange of thoughts on the design of the luxurious item, as it really wasn’t anything which was stocked, not even by the well-known jeweller company Juvelerare-Aktiebolaget Lars Larsson & Co at Jakobstorg.

Jeweller Larsson advertised that they actually undertook everything within honorary presents "from the most simple and extremely cheap to the most elegant " and "orders are accepted, sketches and cost estimates drawn up". Yet one still wonders who contributed with what – who designed this Great Swedish brag telephone, for the staggering price, at that time, of 1000 kr.

He reached the age of 60 years and had, according to his local freemason friends, with their sense for theatrical exaggerations, "the pure distinguished artlessness, which has been and still is the Swedish nobility’s most exquisite decoration ", in itself uniting "bourgeois simplicity and urbane and gentlemanly manner ". And now he was Chairman in almost everything, knew just about all the rich - albeit parsimonious - subscribers, the telephone association jubilated and the battle against Telegrafverket seems to have been important for many.

This was not in the least the case for the fulltime employed and relatively well paid Hilde Torbjörnsson who, for a cost corresponding to 200 daily salaries according to the Charter, signed the purchase order for this extraordinarily odd jeweller’s product. The strong man of the region, the Major, the Baron and Bank Director Bror Samuel von Otter, was not only given it – it almost seems as though he had wanted it.

Thirty-four years later, Ericsson’s unofficial historian, Gustav Collberg was to compile the mile stones of the global company’s then 50-year-old history and was able to conclude proudly conclude that the firm had delivered three luxury telephones, specifically in gold and ivory; one to the Khedive of Egypt, one to the Russian Tsar and one went to Skåne. However, Ericsson’s Russian interests were dispersed due to the violent revolution. The Tsar, whose aged self-rulership had been bathing in unrivalled jewellery splendour, was ruthlessly executed by a firing squad made up of his own men, the Egyptian head of state overthrown by the British, and the energetic Director General Storckenfeldt resigned by death from his belligerent office.

Bror Samuel on the other hand – who had been permitted to grow old and die in his sleep at home in Kristianstad – had no-one at Ericsson to even remember him anymore. Collberg incorrectly and symptomatically enough guessed the renowned Count Posse to be the recipient.

Apparently, then, and despite his exceptional list of merits, the noble Major had lost a final and conclusive battle. For when the local freemason friends’ solemn ceremonies had faded out, only eternal oblivion and the peerless gold regalia remained.

Image texts

1. "He, with the opportunity from childhood days to witness the astonishing significance of the means of communication for the public benefit, eagerly promoted the facilitation of communication and personally overtook the management of the oldest railroad company of the locality and its first telephone association." This is how he, Bror Samuel von Otter, the Baron, and the strong man of Kristianstad, was admiringly described by his local friends at his departure in 1910. Today a name all but forgotten.

2. The coat of arms of the noble family von Otter.

3.Bror Samuel von Otter’ s own proud seal. He had his personal letterhead imprinted with this BSVO.

4. The first Skeleton telephone with hand set became the model not only for the Tsar’s luxury telephone, but also for the immensely popular and style spawning design which came to become Ericsson’s trademark. The fact that it went to the chief person of a small local telephone association, makes one suspect a symbolic connection to the origins of the firm, and all that it could promise for the future. Lars Larsson & Co, 18 carat gold, according to the stamps, while the blue and yellow cord is a little worn, perhaps following the protracted negotiations with the Royal Telegrafverket.